Learning to learn in kindergarten

How metacognition interventions can support all children

The way children think about thinking – their metacognition – is closely related to how well they learn. A new study shows that this link may be present even in the earliest years of schooling and, importantly, that fostering metacognition in early education can boost academic outcomes. This could reduce the learning gap between children from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

The kindergarten metacognition intervention

The study involved 344 kindergarteners aged 5 to 6 and enrolled in public schools in France, where education is mandatory from age 3. Half of the children continued with the regular curriculum, while the other half participated in a metacognition intervention called Learning to Learn in 7 weekly 1-hour sessions.

“Metacognitive teaching might help narrow achievement gaps if integrated consistently into early education.”

Children in the intervention group made greater progress in understanding how the brain works than those who didn’t receive the intervention. They also showed greater improvement in their learning, particularly in arithmetic. It was encouraging that children from a lower socioeconomic background seemed to benefit the most 3 months after the intervention, especially in terms of their grammar skills. This delayed effect suggests that metacognitive teaching might help narrow achievement gaps if integrated consistently into early education.

How teachers can foster metacognition

The Learning to Learn intervention was structured around three pillars of metacognition. These pillars guide strategies that teachers can use in their classrooms.

1. Metacognitive knowledge

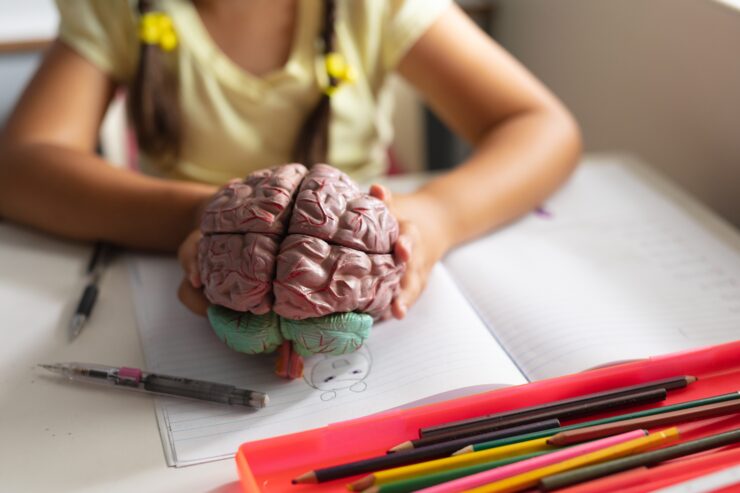

Children learned about the brain and how it learns, with visual supports and fun hands-on activities like building networks of neurons using yarn. These activities demystified the learning process and shed light on how and why we learn—not just what we learn. The aim was to teach children how to recognize their own strengths and weaknesses as learners, and to help them understand how cognition works.

2. Metacognitive skills

Children learned planning, monitoring, and self-evaluation strategies, and were able to see that strategies are like tools in a toolbox. Images helped children understand and use those strategies. For example, a picture of a detective with a magnifying glass prompted children to think about the effectiveness of the procedure they were following, and a picture of children walking up steps encouraged them to think about how to progress in their learning.

3. Metacognitive reflection

Children learned questions they can ask themselves to guide independent learning. For example: What is the goal of this activity? What’s the best strategy to solve this? Is everything going as planned? Should I try another way? How can I do better next time? This helped support children’s general metacognitive awareness.

During each session, children applied these strategies to different tasks, such as solving puzzles, identifying letters, and completing simple math problems. The goal wasn’t to teach children new content, but to influence how they approach learning. Although these concepts may seem complex, they can be fully accessible to young children, including those who struggle the most, through playful activities, visual supports, and simple explanations. For instance, children in the intervention were told at the beginning of each session:

“We try to learn how to learn so we can learn better. To do that, we look at the brain, because it’s thanks to our brain that we can learn, and it’s important to know how it works to learn well. We also talk about the best tools, techniques, and strategies to use before, during, and after an activity. And we ask ourselves lots of questions to think about what we are doing and to help us learn better.”

“Fostering metacognition from the earliest years could help reduce educational inequalities.”

The intervention was designed by researchers, but implemented in close partnership with teachers, who helped adapt the materials, engage the children, and ensure that the recommendations fit the reality of the classroom. Collaboration like this between researchers and teachers is powerful. We also need more professional development opportunities and resources for teachers focused on metacognition. Fostering metacognition from the earliest years could help reduce educational inequalities, closing the learning gap between children from different socioeconomic backgrounds.

Footnotes

This article was developed as part of the Educator Initiative led by the Trainee Board of the International Mind, Brain, and Education Society, with support from the Jacobs Foundation. Mélanie Maximino-Pinheiro was an author on the soon-to-be published paper described in this article. Learn more about bridging the gap between the science of learning and what happens in classrooms from UNESCO.