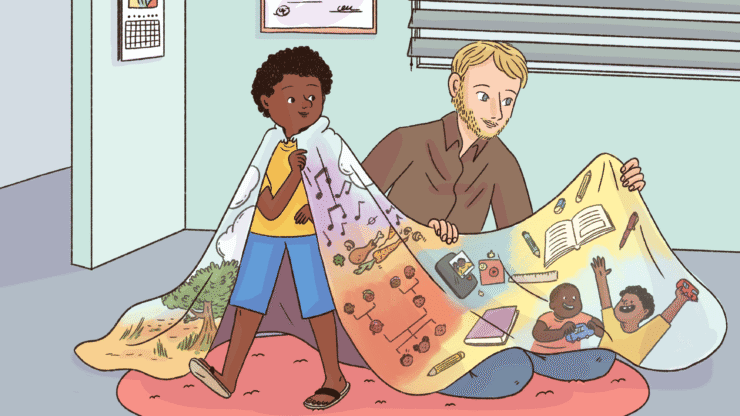

The developmental scientist showing how culture influences children

Roman Stengelin is helping to build a culturally sensitive understanding of how children grow

Roman Stengelin studies how children navigate and thrive in their social worlds. He combines approaches from experimental and cross-cultural psychology to examine how children in different communities develop social and cognitive skills. Annie Brookman-Byrne finds out more.

Annie Brookman-Byrne: What are you trying to understand about children’s social worlds?

Roman Stengelin: Humans are social by nature. Children everywhere rely on their social and cultural worlds to grow into content, capable, and valued members of their communities. I explore how children make sense of their own and others’ thoughts, how they learn to cooperate, and what drives them to help others.

“Children everywhere rely on their social and cultural worlds to grow into content, capable, and valued members of their communities.”

But the social and cultural environments children grow up in can be vastly different. To fully understand and support child development, we need to study and compare children’s behaviors and experiences across diverse cultural communities. I study these questions in both urban Germany and diverse communities in Namibia—and hope to expand this work to other parts of the world.

ABB: How will your cross-cultural research help children?

RS: If we want to provide effective supports and interventions for child development, we must first understand the unique and diverse worlds children grow up in. A one-size-fits-all approach not only risks overlooking children’s full potential, but can also be detrimental to children, caregivers, and their communities. In the coming years, I aim to deepen our understanding of childhood socio-cognitive development in peer groups. These insights could help shape learning approaches that harness children’s culturally-grown social tendencies and skills.

More broadly, I believe that cross-cultural research—especially in communities traditionally underrepresented in developmental science—is essential for reminding us of the deeply cultural nature of child development. Too often, developmental scientists assume research findings apply to generic “children,” overlooking the cultural foundations of the research. No child grows up in a cultural vacuum, and we owe it to the participants in our studies and their communities to take culture seriously.

“Too often, developmental scientists assume research findings apply to generic “children,” overlooking the cultural foundations of the research.”

ABB: How has child development research changed over time?

RS: For a long time, researchers assumed that many aspects of child development were universal. In recent decades, however, cross-cultural research has revealed striking variations in young children’s behaviors and experiences across different societies. These findings challenge the global relevance of a “culture-blind” developmental science, while opening up exciting opportunities for international collaboration. By moving beyond a narrow focus on children from Western, affluent communities, we can build a more inclusive and scientifically accurate understanding of how children worldwide grow and develop.

At the same time, globalization and digitalization are reshaping childhoods virtually everywhere, influencing how children learn from and engage with their social worlds. With globalization converging children’s cultural experiences through shared media or schooling faster than ever, there is an urgent need for a cross-cultural agenda. If we truly want to understand how children grow and thrive in different parts of the world, there’s no time to waste.

“There is an urgent need for a cross-cultural agenda.”

ABB: What are the biggest mysteries in developmental science?

RS: A key challenge in childhood research is understanding how study findings generalize to children’s real-world behaviors and experiences. Experimental studies often focus on social cognition in what we believe to be its simplest form. Typically, we examine dyadic interactions between two children or between a child and a caregiver. However, in everyday life, children engage in far more complex and dynamic group settings. So how do these dyadic skills and behaviors we’ve measured manifest themselves in day-to-day life?

This issue is particularly important from a cross-cultural perspective, as dyadic interactions appear to be more common in Western, industrialized communities. With this in mind, my colleagues and I plan to systematically compare various aspects of social cognition across dyadic and small group interactions, seeking to identify any differences and continuity between the two.

ABB: What are your hopes for the future of child development research?

RS: In recent years, developmental science has undergone a major shift with the rise of open science. Our research is becoming more transparent and thus also more credible. I hope to see similar progress in addressing the field’s cultural blind spots. This means not only studying a more diverse range of communities, but also contextualizing our findings—especially when working with “convenience samples” living near the researchers. Too often, cultural psychology is treated as a separate subfield rather than being integrated into a supposedly “culture-free” mainstream.

I also hope that we will succeed in diversifying not only our research participants, but also the researchers conducting the science. To that end, we recently launched a student exchange project with the University of Namibia where we fund cross-cultural research training and thesis projects for students in Germany and Namibia. I am excited to see how this initiative unfolds in the coming years—and I especially hope to see some of our students embark on lasting careers in developmental science.

Footnotes

Roman Stengelin is a Senior Scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany. His research explores the developmental foundations of childhood social cognition, adopting both developmental and cross-cultural approaches. Working with diverse communities in Namibia, he investigates how children’s everyday cultural experience shapes their understanding of others’ minds and behaviors, as well as their prosocial and collaborative tendencies. Roman is a 2025-2027 Jacobs Foundation Research Fellow.

This interview has been edited for clarity.